Científicos de la UCLA (Universidad de California en Los Angeles) han descubierto una forma nueva de transferencia energética desde el viento solar a la magnetosfera de la Tierra. El descubrimiento podría mejorar la seguridad y fiabilidad de las naves espaciales que operan en la alta atmósfera.

Científicos de la UCLA (Universidad de California en Los Angeles) han descubierto una forma nueva de transferencia energética desde el viento solar a la magnetosfera de la Tierra. El descubrimiento podría mejorar la seguridad y fiabilidad de las naves espaciales que operan en la alta atmósfera.En palabras de Larry Lyons, profesor de la UCLA "es como si hubiera algo más que el sol calentando la atmósfera. Es equivalente a encontrar que todo se calienta más cuando se pone el sol"

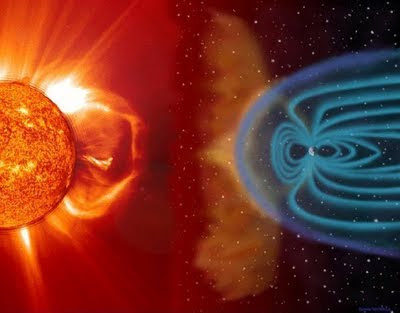

El sol, además de radiación, emite un flujo de partículas ionizadas llamado viento solar que afecta a la Tierra y al resto de planetas del sistema solar. El viento solar, que transporta partículas desde el campo magnético del sol, conocido como campo magnético interplanetario, tarda tres o cuatro días en alcanzar la Tierra. Cuando las partículas cargadas se acercan a la Tierra, toman la forma de la magnestofera una región altamente magnetizada que rodea y protege la Tierra.

Las partículas cargadas originan corrientes electricas que modifican sustancialmente la magnetosfera y causan problemas en los satélites, redes energéticas y comunicaciones.

Se pensaba que la velocidad de transferencia energética estaba controlada sobre todo por la dirección del campo magnético interplanetario. En palabras de Lyons, "cuanto más próximo hacia el sur apunte el campo magnético, más grande será ña velocidad de transferencia de energía, y tanto más cuanto más fuerte sea el campo magnético en dicha dirección. Si el campo magnético está a la vez dirigido hacia el sur y es grande, la velocidad de transferencia es aún más grande".

Sin embargo, Lyons y sus colegas han encontrado subtormentas magnéticas cuando el campo interplanetario estaba apuntando hacia el norte. Este descubrimiento abre nuevas perspectivas, dado que no es el comportamiento que cabría esperar.

UCLA atmospheric scientists have discovered a previously unknown basic mode of energy transfer from the solar wind to the Earth's magnetosphere. The research could improve the safety and reliability of spacecraft that operate in the upper atmosphere.

UCLA atmospheric scientists have discovered a previously unknown basic mode of energy transfer from the solar wind to the Earth's magnetosphere. The research could improve the safety and reliability of spacecraft that operate in the upper atmosphere."It's like something else is heating the atmosphere besides the sun. This discovery is like finding it got hotter when the sun went down," said Larry Lyons, UCLA professor.

The sun, in addition to emitting radiation, emits a stream of ionized particles called the solar wind that affects the Earth and other planets in the solar system. The solar wind, which carries the particles from the sun's magnetic field, known as the interplanetary magnetic field, takes about three or four days to reach the Earth. When the charged electrical particles approach the Earth, they carve out a highly magnetized region — the magnetosphere — which surrounds and protects the Earth.

Charged particles carry currents, which cause significant modifications in the Earth's magnetosphere and wreak havoc on satellites, power grids and communications systems.

It was thought that this energy transfer rate was primarily controlled by the direction of the interplanetary magnetic field. According to Lyons "the closer to southward-pointing the magnetic field is, the stronger the energy transfer rate is, and the stronger the magnetic field is in that direction. If it is both southward and big, the energy transfer rate is even bigger."

However, Lyons and colleagues have found substorms when the interplanetary magnetic field was staying northward. The discovery opens new perspectives and problems, because this behaviour was unexpected.

Tomado de /Taken from UCLA

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario